Jump To:

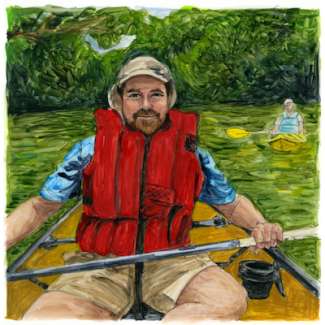

Ross Andrews

Ross Andrews, the first Director of Walnut Creek Wetlands Park, was an environmental scientist, an educator, and lover of nature. He worked closely with Dr. Norman Camp, Betty Camp and Partners for Environmental Justice on the campaign to establish the park at Walnut Creek Wetlands, and co-founded the Neighborhood Ecology Corps with Randy Senzig in order to encourage neighborhood youth to be involved with the environment.

A native of Charlottesville, Virginia, Ross grew up loving nature as he participated in Boy Scout backpacking trips in the Blue Ridge mountains and canoeing. He spent time under the giant oaks and poplar trees as an undergraduate student at UNC Chapel Hill where he wrote poetry that was eventually published in a volume titled, “Wild Peace.” By trade, he was an environmental scientist, but in his heart, he was an educator and lover of nature.

Ross was a mentor to youth, and loved creating outdoor learning environments so young people could develop personal connections with nature. He co-founded the Neighborhood Ecology Corps with Randy Senzig in order to encourage neighborhood youth to be involved with the environment. To this end, he worked with school systems, state parks and the Triangle Land Conservancy to get kids outside, including engaging students in community service-learning projects in the Walnut Creek Wetlands through Partners for Environmental Justice (PEJ).

As a close colleague of Dr. Norman Camp, Ross organized restoration tree planting, sometimes navigating his canoe deep into the creek to plant saplings. He participated in the early creek clean ups as well, and planned environmental education programs for community members.

Ross was the Executive Director of the Center for Human-Earth Restoration (C-HER), a non-profit he co-founded based in part on a belief that “if people expand their connection to the Earth, they will find deeper joy in time outdoors and, in turn, will protect the Earth and live with it wisely.”

Ross died unexpectedly in 2013 at age 39. The Ross Andrews Trail at Walnut Creek Wetlands Park is named in his honor.

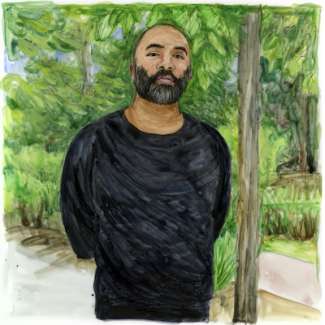

Cashew Banks

Cashew Banks, and aspiring filmmaker, is a frequent visitor to Walnut Creek Wetlands Park.

I’m from Salisbury, North Carolina, it’s about 30 minutes from Charlotte. Salisbury’s really, really small. You can drive past it

I’m still kind of fresh in Raleigh. I’m still looking around, finding different parks. I live five minutes down the street from WCWP. I come here a lot, I walk the trails. After I started volunteering at the food bank in Raleigh, I just wanted to explore the community more, and so I came out here to enjoy the animals, like Mr. Thoreau.

I want to make feature films. I do want to capture a couple of documentaries, but I want to put my own twist on it, do like an exaggerated version of what it is, kind of a mixture of both? Find that lane that’s in between.

The flooding-- I work at a heavy machinery company, they sell really big construction machines.

Close to my job there's a bridge that I go under every time I leave work, and it can rain for five minutes, and that whole thing is covered in water. You can't even drive through it. You'll see trucks turn around. Watch Cashew tell his story.

Derrick Beasley

Derrick Beasley, a multi-disciplinary artist from Durham whose work deals with Black people and their relationship to the environment, created an artwork for WCWP that is a dedication to the power of collective action and organizing around wetlands.

My artwork is untitled, but I've been calling it The Monolith. It's a sculpture. It has a technical description of the gravel wetlands and a narrative description that speaks to the history of the neighborhood and its fight for environmental justice. It has a window where people can look at that narrative, and see through the window to the gravel wetland and imagine possibilities for our relationship with the environment.

I walked through the neighborhood with neighbors, spoke with folks and attended some community meetings and community days. I also did a survey to get folks’ idea of what their vision is for the future of their neighborhood in terms of the relationship to the environment. I used this data to inform the narrative and design.

Folks just want to be able to access the environment in a safe and clean way, I think that's the biggest thing. There are a lot of false assumptions around Black folks and our relationship to the environment. My conversations with the community really dispelled that misconception and encouraged me in my own practice.

For the engineering and fabrication, I partnered with Jim Gallucci Sculpture out of Greensboro, NC and consulted with city engineers.

Derrick Beasley is Nashville, TN born and Durham, NC raised, with a Bachelors in Sociology from NC Agricultural and Technical State University and a Master’s in Public Administration and Policy Analysis from Georgia State University. He says, “I am self taught artist who approaches my creative practice with the same rigor as I did my undergraduate and graduate studies.

I create out of a sense of responsibility to my community and a desire to answer three persisting questions. “What would make this world better?”, “How can I work to create it today?” and “what do I need to heal in myself to create it”. My work is informed by the intersection of my identities as a Black, Cisgendered, heterosexual man, my self proclaimed nerd-dom and obsession with science fiction and being from the American South. I want to show that the radical new world so many of us are fighting for is actually a basic human experience.”

Find out more about Derrick’s public artwork

Derrick Beasley's website

Desiree Bolling

Desiree Bolling is a member of St. Ambrose Congregation and an advocate for those who don’t have a voice, with a focus on health. She served under four North Carolina Governors on boards for Developmental Disabilities and Autism and advocates for people who are blind or have low vision.

I moved to Raleigh when I was about 50. I knew my purpose was to be an advocate in the community. I started getting involved with “Project DIRECT” (Diabetes Intervention Reaching and Educating Communities Together, a program of the Federal Center for Disease Control) which continued as the nonprofit “Strengthening the Black Family.” I was involved in raising awareness of health priorities and chronic diseases that particularly affect the Black community.

My focus is health care. I served under four North Carolina Governors on boards for Developmental Disabilities and Autism. I advocate for those who don't have a voice.

I also advocate for people who are blind and with low vision. I decided to be a voice and a mentor, and speak out, and the only way I could do it, I had to start with myself. People are not educated about these disabilities, so I use myself as a model. As a child, I was diagnosed with childhood glaucoma. A lot of people lose their vision now due to diabetes. They have a really, really, really hard time adjusting.

At the health center, I do a vision education day. If a patient calls and says, I can’t take my blood sugar, I encourage them to use the tools they have, like large print outs, getting a blood pressure monitor, trying to help people change their eating habits and their lifestyle.

I live in Southeast Raleigh not too far from St. Ambrose. I went with a friend to St. Ambrose and it was the first time I really felt, this is the right place. Father Taylor sees my independence and he knows I will try to work things out before I will ask for help.

At St. Ambrose, I am really proud and excited about the Labyrinth. I hear the birds, I can still hear a little bit of traffic, but I just tune into nature. Even though I can’t see, I hear and see and feel. It’s a kind of sight. The Labyrinth gives you spiritual direction, you’re close to nature but you’re close to God, you can feel His presence and shut everything out around you.

You can get this from nature too. At Walnut Creek, sitting outside with just a little wind, I could really appreciate hearing people engaged around me and the beauty of it.

Sarah Brim

Sarah Brim is a graduate of North Carolina State University, working as a park attendant and environmental educator. To achieve environmental justice, she helps build/rebuild relationships between nature and historically marginalized communities.

I work at Walnut Creek Wetland Center, I am a park attendant. We keep the park clean. We inform the community about environmental engagement and environmental justice, giving a little history about the park, trying to get people to grow and love the nature that they live in. As well as cleaning up invasives, or caring for animals. It's super cool! This is year two for me.

I think my favorite part is the community engagement, especially being in a minority area, seeing Black and Brown people come to learn more. There's often a disconnect between the natural world and these communities, and I think it's really cool that Walnut Creek can bring that to them.

I attended North Carolina State University with a BA in Biological Sciences and a minor in Africana Studies. I hope to work in environmental justice. I love environmental education and am trying to build and rebuild that relationship for people, especially people that look like me, because you don't see that often. I think education can be very powerful in terms of advocating for environmental justice, so that's what I hope to do.

Glendia Bryson-Jacobs

Glendia Bryson-Jacobs (here with her grandson, Cayden Saunders) has been participating in Walnut Creek cleanups since the park was founded. She and her three children have a lifelong connection with the Wetland Center through membership in Top Ladies of Distinction & Teens of America, a WCWP community partner.

I live in Kingwood Forest, which is close to St. Ambrose Episcopal Church of which I have been a member for over 30 years. I have participated in the Big Sweep clean-ups as a member of Top Ladies of Distinction. I was present at the groundbreaking for the Walnut Creek Wetland Center, along with Top Teens of America, the youth component of Top Ladies. We have partnered with Walnut Creek Wetland Center in education, service and clearing invasive foliage. I have three children who were all members of Top Teens, and we were close to the Camp family.

Top Teens and Top Ladies were part of the very first Privet Pull, quite a few years ago. That's where privet hedges, which are invasive, are actually pulled up before they get too mature. There were sections of the wetlands that were just overrun with them. The Teens went in one Saturday with other community helpers and began to pull them out. It was hard to do. Someone said to one of our small in stature members, ‘You can't do that.’ She fitted and leaned on the tree pullers and popped the sapling up out of the ground. Then she said, ‘Now, who can't do this?’

Growing up in the mountains of Western North Carolina, we were always outside, working in and growing our own gardens. We believed in our own sustainability out of necessity. We ate the foods we grew, we shared, prepared and preserved. When I came to Raleigh, that was something I didn't have a chance to do, at first.

When I married, we lived in Kingwood Forest, then we moved out of the city, so we could have a garden. My children were raised eating what we grew, shared, prepared, and preserved. However, after over thirty years we returned to our first neighborhood. We still have a garden outside of the city and we harvest seasonally to support our pantry.

Walnut Creek Wetland Park and Education Center provides the opportunity for the community to learn about the importance of respecting and preserving our resources. I've always felt like it's important that we take care of the earth because the earth takes care of us. Watch Glendia tell her story.