Jump To:

Artist Deborah Aschheim has created a series of 30 portraits of community members who have a connection to the Walnut Creek Wetland Park. The artworks depict the faces and narratives of people who love the park, work at the center, or have contributed to the creation or ongoing story of the park.

Visitors to the Walnut Creek Wetland Center can view the portraits during park hours. To view the portraits online, scroll through the image galleries below and follow the links to view the full profile of each community member.

Ross Andrews, the first Director of Walnut Creek Wetlands Park, was an environmental scientist, an educator, and lover of nature. Read more about Ross Andrews.

Desiree Bolling is a member of St. Ambrose Congregation and an advocate for those who don’t have a voice, with a focus on health. Read more about Desiree.

Sarah Brim is a graduate of North Carolina State University, working as a park attendant and environmental educator. To achieve environmental justice, she helps build/rebuild relationships between nature and historically marginalized communities. Read more about Sarah.

Cashew Banks, and aspiring filmmaker, is a frequent visitor to Walnut Creek Wetlands Park. Read more about Cashew.

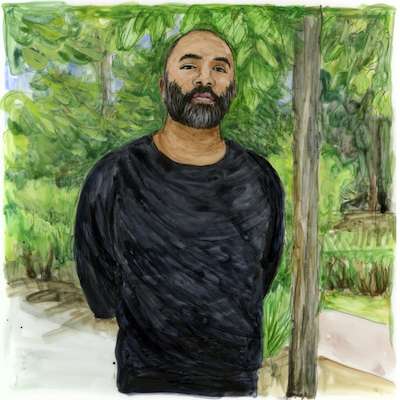

Derrick Beasley, a multi-disciplinary artist from Durham whose work deals with Black people and their relationship to the environment, created an artwork for WCWP that is a dedication to the power of collective action and organizing around wetlands. Read more about Derrick.

Glendia Bryson-Jacobs (here with her grandson, Cayden Saunders) has been participating in Walnut Creek cleanups since the park was founded. She and her three children have a lifelong connection with the Wetland Center through membership in Top Ladies of Distinction & Teens of America, a WCWP community partner. Read more about Glendia.

Dr. Norman and his wife, Betty played a key role in galvanizing the community to support the construction of Raleigh’s Walnut Creek Wetland Center to alleviate flooding in Biltmore Hills and Rochester Heights. Read more about the Camp family.

Adrienne Chalmers experienced flooding as part of growing up in Biltmore hills. She went on to work for Wake County Public Schools and is now the After School Director at Lee Brothers Martial Arts. Read more about Adrienne.

Adrian Chamberlin is a Recreation Leader at Walnut Creek Wetlands Park, and an instructor for Neighborhood Ecology Corps Year 1 Cohort. Read more about Adrian.

Tzu Chen is an architectural photographer and a licensed architect, who lent his skills to documenting the Raleigh Stories installations and Derrick Beasley’s artwork for WCWP. Read more about Tzu.

Charles Craig is the Assistant Director of Raleigh Parks and Natural Resources Division: 10,000 park land acres/200 parks, 120 miles of greenway, 81 athletic fields and 96 playgrounds. Read more about Charles.

Julia Kay Daniels has fond memories of growing up playing in the woods near the park, but she also remembers Walnut Creek flooding neighbors’ homes. Read more about Julia.

Amin Davis is an Environmental Scientist for the NC Division of Water Resources, Board Member of Partners for Environmental Justice and Friend of the Walnut Creek Community. Read more about Amin.

Lina Edwards lives near Walnut Creek Wetlands Park and is in Year Three of the Neighborhood Ecology Corps (NEC). Lina is considering a career related to ecology. Read more about Lina.

Corie Griebel is a Master’s Student at NC State studying Natural Resources. Corie works part-time at WCWP, teaching programs that help kids connect with nature. Read more about Corie.

Ivanna Solis Gutierrez lives near Walnut Creek Wetlands Park and is in Year Two of the Neighborhood Ecology Corps (NEC). Ivanna is hoping to pursue life as a marine biologist. Read more about Ivanna.

Stacie Hagwood was Director of WCWP from 2015-2022, carrying forward Dr. Norman and Betty Camps’ vision for the park and education center. After retiring, Stacie returned as a part-time employee. Read more about Stacie.

Cypriane Jacobs lives near Walnut Creek with her son Cayden. She has participated in creek cleanups and trash pickup along the park trails. Read more about Cypriane.

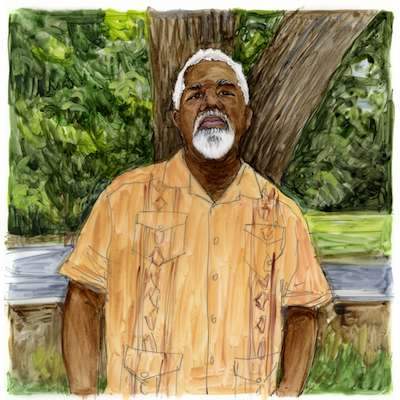

George C. Jones, Jr., the Executive Director of Partners for Environmental Justice (PEJ). He is working to honor Dr. Norman Camp’s vision for WCWP while he leads PEJ into the next era of environmental stewardship and restoration. Read more about George.

Kasey and her family were visitors to Mud Day 2023 at Walnut Creek Wetlands Park. Read more about Kasey.

Celia Lechtman is the Assistant Manager at Walnut Creek Wetlands Park. Read more about Celia.

Harold Mallette grew up in Biltmore Hills. His concern for environmental justice grew out of his parents’ friendship with Dr. Norman and Betty Camp. Read more about Harold.

Sheryl McGlory is an Environmental Education Programs Manager with the City of Raleigh’s Nature Preserves and Programs team. Read more about Sheryl.

Enid Patterson, a long-time congregant at Saint Ambrose Episcopal Church, lives in Biltmore Hills. She is an active volunteer with Urban Ministries of Wake County and the Helen Wright Center for Women. Read more about Enid.

Elaine Peebles-Brown lives in the first house built in Rochester Heights. She is an advocate for excellence in health care for the Southeast Raleigh Community. Read more about Elaine.

Kyleene Rooks, Park Manager at Walnut Creek Wetlands Park, has an appreciation for the history of the park and its deep community involvement. Read more about Kyleene.

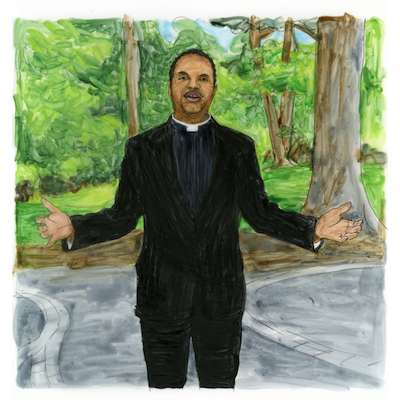

The Reverend Robert Jemonde Taylor is the eleventh rector of St. Ambrose Episcopal Church. His commitment to environmental justice and racial equality, and his personal connection to the land, deeply inform his ministry of resurrection and transformation, and his civic involvement. Read more about Reverend Taylor.

Karyn C. Thomas, a member of St. Ambrose Episcopal Church, is a native resident of the historic South Park Community, growing up during her youth in Biltmore Hills. Read more about Karyn.

Katrel Thomas is studying to be a mental health counselor. She is passionate about the importance of mental health awareness for minority communities. Read more about Katrel.

Josie Wright and her mother, Rosie, live in Clayton and are members of St. Ambrose Congregation. They are very in tune to how important the wetlands are, not only for their church community, but for everybody around us. Read more about Josie.