Jump To:

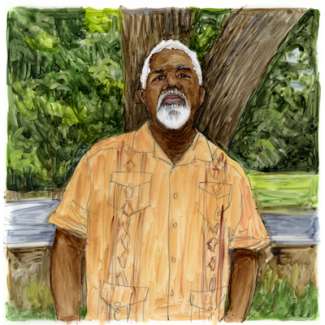

Harold Mallette

Harold Mallette grew up in Biltmore Hills, moving to Waters Drive shortly after the neighborhood was developed. His concern for environmental justice grew out of his parents’ friendship with Dr. Norman and Betty Camp.

I’ve been a mental health, family counselor, and then a substance abuse counselor. Now I do juvenile justice counseling. There’s always been an ethos of service in my family.

I am the son of David and Mary Mallette. My parents were educators out of Robeson County, and then Wilmington. We moved here from Wilmington when I was seven, in 1967. My father and Dr. Norman Camp were friends, along with Carolyn Winters with the environmental people. They help to initiate concern about the Wetland Park.

First of all, nobody was calling it “wetland,” it was sewage. It ended where State Street comes down to Bunche Drive, at a big pipe, and sewage and water ran through that. As kids we played in little platoons of concrete. We would go out in those little platoons and ride up and down the water.

Q: Was it unhealthy, though?

H: Definitely.

We did not know how unhealthy it was. It was a part of play growing up. As we became teens, we became more and more aware that this is really sewage. Most of the time it didn’t smell bad. It looked weird. Green, Brown. But the water, because of the elevation, would often come in and flush that all out so it looked like regular water. The adults began to talk about it. As the water began to come regularly, it threatened to flood the church.

We belonged to St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Wilmington, it was the first African American Episcopal Church in North Carolina. We came to St. Ambrose in 1967 or 68. I went to Fuller Elementary. This whole neighborhood was 3 or 4 years old. It was something to really be proud of, it still is.

I had never seen a neighborhood specifically developed and planned for African American homeowners. In some neighborhoods, there may be 10 or 20 houses owned by African Americans. But there were at least 100 houses in Biltmore Hills and Rochester Heights. It was something to behold. It was a real, thriving community at that time. There was a grocery store, 2 gas stations, a cleaner.

Most of the homeowners were veterans who had lived in different parts of Raleigh, and they finally gotten to where they could utilize the GI Bill to get financing. That's how this neighborhood developed.

Sheryl McGlory

Sheryl McGlory is an Environmental Education Programs Manager with the City of Raleigh’s Nature Preserves and Programs team. One of the projects she works on is the Neighborhood Ecology Corps (NEC), based out of Walnut Creek Wetland Park.

When I found the role I'm currently in, I thought, that's it. That's my job. I love the work that I do.

One of the programs I work with is the Neighborhood Ecology Corps (NEC), based out of Walnut Creek Wetland Park. About 80% of my job is behind the computer, but the NEC gives me a chance to put on boots or get muddy or run through field with kids.

The Neighborhood Ecology Corps (NEC) was created by the Center for Human-Earth Restoration (CHER) and transitioned to be a City of Raleigh program in 2021. It’s a three-year environmental literacy program.

In Year One of NEC, we're working on gaining comfort in the outdoors. Students come with different levels of experience. We’ll have some participants who are not super comfortable around bugs, are a little hesitant about putting boots on and getting in mud, and aren't accustomed to spending an entire day outdoors.

By the time we get to Year Three, that’s second nature. We see a change in comfort level and we see a real change in the understanding of the impact they can have as individuals. By Year Three, we're focusing on building skills to be active, involved, engaged citizens: being able to identify connections between environmental issues and their communities and their personal interests, figuring out how to really speak to those.

The most recent Year Three cohort created a video project focused on solid waste and littering in streams. The messaging is all came from the students. It’s a shift to content being driven by the participants.

If we can help young people develop the skills to communicate about things that they care about, and connect their communities to these topics, we can expand their impact. Watch Sheryl tell her story.

Enid Patterson

Enid Patterson, a long-time congregant at Saint Ambrose Episcopal Church, lives in Biltmore Hills. She is an active volunteer with Urban Ministries of Wake County and the Helen Wright Center for Women.

I have been going to St. Ambrose for over 50 years. I came here in 1969.

We're more inclusive now. When I came here, the church was very strict, they had rules and regulations, you couldn’t clap in the church. We would not have had this kind of music before. We now have the Stations of the Cross, which are Black icons, which we didn't have before. We're getting a little bit more progressive and to me, it's a more welcoming church.

We have embraced the community. We've reached out and done things. We associate with Fuller Elementary School up the road. The Episcopal Church women have collected a lot of things for women who are struggling, like diapers and stuff like that. We are doing things for St. Augustine’s University, and for the Urban Ministries and the Helen Wright Center for Women. I am involved with these ministries.

This labyrinth here is the only one in Southeast Raleigh. Anybody can come here, walk around. There is a box with information about the labyrinth and what it stands for.

I live in Biltmore Hills. This area was built for Black people. All the streets in Biltmore Hills are named after Blacks. I live on Campanella, which is named after Roy Campanella. In my neighborhood, I haven’t seen that many changes yet, but they're coming. People are moving out and more whites are moving in. People here in Rochester Heights have experienced flooding, and some people have had to move out, from what I understand.

I was in New York before I moved here. I love Raleigh. I love the quietness, you're not racing, go, go, go. You have peace, you have quietness and culture. Most of all, people are friendly, they make you feel welcome.

Raleigh is growing. I've seen streets that weren't paved, now are paved, people moving in, if they want to associate with the Black neighborhood, they have to reach out and they will be welcomed. Watch Enid tell her story.

Elaine Peebles-Brown

Elaine Peebles-Brown lives in the first house built in Rochester Heights. She is an advocate for excellence in health care for the Southeast Raleigh Community and served for 18 years on the Advanced Community Health Center board, chairing the board for 4 years.

Rochester Heights, where I live, was a brand-new subdivision built in the late 1950s. It was on the outer edge of Raleigh, at the time not even within the City of Raleigh.

I was only eight years old when building began. I learned that it was the first African American subdivision in Raleigh, and I was proud because my dad and his company had been a part of it, doing the masonry work on all the homes. In Rochester Heights, they did the brick work you see on all these streets that are named after famous African American people.

We were the first ones to move in. He finished our home, and after we moved into our home, people would drive through the neighborhood and marvel in astonishment. It was a first, so there was a lot of excitement, and a lot of pride.

All the houses are different. On Calloway Drive, all the houses have least three bedrooms, and most of them have basements. The owners were hard working, young Black families, mostly in their 30s. They were two income families, where the mom and the dad both worked very hard. In some instances, parents worked more than one job to achieve the goal of home ownership.

So, it was a first and it was really an accomplishment. It was something that, community-wide, people were proud of. Many of the young families were moving in and having their first babies at the same time.

Until very recently, Garner Road was often flooded and you couldn’t get through. My aunt (my dad’s sister) and my uncle lived at the corner of Garner Road and Bailey Drive. My uncle was one of the master brick masons who built their house and worked on the surrounding houses. They actually had to abandon their home because they were flooded out completely. Despite their strong desire to stay in Rochester Heights, they had to relocate to another neighborhood in Raleigh. It was very, very painful for them to leave the home and community they had helped build.

When Walnut Creek Park opened, I was so happy that we had a wonderful meeting place, and we could have wedding receptions and parties right here in our own community, representing our neighborhood

Kyleene Rooks

Kyleene Rooks, Park Manager at Walnut Creek Wetlands Park, has an appreciation for the history of the park and its deep community involvement. Her program focus is informed by this standard of citizen agency.

I am from the Shenandoah Valley of northern Virginia. I grew up inspired by the outdoors. I started as a biology/pre-medical student at North Carolina A&T, but I wanted a summer internship that would keep me outdoors.

I took the risk of working with an AmeriCorps conservation crew program. It was completely out of my comfort zone, 10 weeks of camping in summer in NC. Through that program, I gained language and resources for the type of work I was most interested in. Over the last 10 years I've worked in agricultural and urban management, in public service with local government or non-profit organizations. I enjoy interacting with the communities I serve, coming from a position of listening rather than telling. Raleigh had City-wide initiatives that supported my career goals and was the perfect size for me to grow into.

One thing I’ve learned to appreciate is how invested the surrounding community and larger citizen base is at WCWP, how deep its history runs and is well remembered. This property’s history was the entire reason I'd applied to WCWP. I am very grateful that there are people as invested in this space as I am, who also look like me. Natural resource professions are a predominately white, male field, and I didn’t realize how much I felt the lack of representation. Now, I get to be a part of creating greater representation in a way that feels so much bigger than myself.

Raleigh has embraced the standard of citizen agency, so I get to engage with people on a variety of topics. WCWP functions as a community center: we're the face of many Raleigh projects, answering questions and providing resources for projects even outside of our scope. I find it to be some of the most exciting and rewarding work I get to do!

At WCWP, we have some regular events we hope to grow. Our Big Sweep clean-ups, 100 volunteers cleaning up over a ton of trash, are the first Saturdays in April and September. Our free, annual Mud Day event gets kids out and in the dirt— we see 500 people on the 3rd Saturday of August. And our upcoming 2nd annual MLK Service Day, where we will host another Japanese stilt-grass pull, which helped helps new baby trees and native plants pop up in place of the invasive plants.