Jump To:

International Comparison

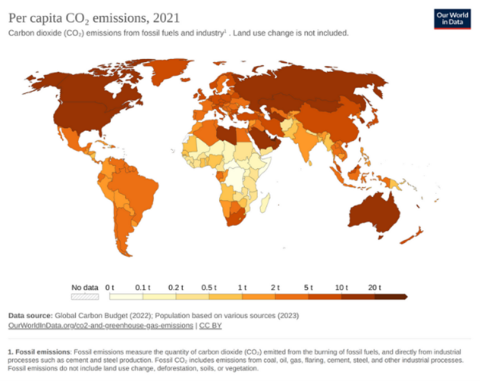

The difference in GHG emissions between places that allow more people to live in walkable areas served by transit and those that strictly limit how many people can live in a neighborhood are significant. This can be seen by comparing carbon emissions in the United States with other counties with similar levels of development. For instance, the average person in the United States produces more than 13 tons of carbon annually, according to the World Bank. The average person in Switzerland uses less than a third of that amount.

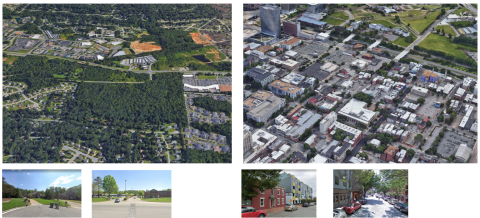

Consider Two Different Neighborhoods

| Neighborhood | Edge of Richmond | Downtown Richmond |

| Zip Code | 23313 | 23219 |

| Typical Housing | Detached houses on large lots | Apartments, townhouses, detached houses on small lots |

| Transit and Walking | No transit, walking difficult or impossible due to distance and conditions | High levels of transit, walking is easy because distances are short and walking is comfortable and safe |

| Driving | Trips are much longer on average because of distance between typical origins (where people live) and destinations (workplaces, shopping, parks, schools) | Trips are shorter on average because origins are close to destinations |

| GHG Emissions Per Person | 68.6 tons per year | 24.2 tons per year |